Real estate contracts contain covenants and warranties that the parties sometimes want to enforce after the sale has been concluded. Whether or not they are still enforceable is determined by whether the covenants were “merged in the deed.” The idea is that, once the Seller grants and Buyer accepts the deed, the deed is conclusive and all bets are off. The general rule is that any covenants in a contract between the parties are merged into the deed. If a covenant is not performed, then the rights of the parties depend on the terms of the deed. If the deed does not discuss the covenants, then whether these covenants survive and remain enforceable after closing depends on the intent of the parties. The starting point for figuring out the party’s intent is the language of the deed. When a provision in a deed is certain and unambiguous it prevails over an inconsistent provision in a contract of purchase pursuant to which the deed was given. Sacramento real estate attorneys commonly see situations where the intent is clear – the contract states whether the conditions survive, or do not. More troubling is the case where the contract is not so clear.

In Rams Gate Winery, LLC v. Joseph G. Roche, Rams Gate bought a Sonoma County winery property from Roche. As part of the agreement, the Roches agreed to provide

“[w]ithin ten days of the Effective Date” “written disclosure” of any “information known to Seller” regarding violations of “building, zoning, fire, health, environmental statutes, ordinances or regulations; [and] any known geological hazards; … soil reports, … geotechnical reports, … and all other facts, events, conditions or agreements which have a material effect on the value of the ownership or use of the Property….”

Escrow closed, and eventually the Buyer learned that there was a fault running through the property that limited its development. The Buyer claimed that, prior to entering the agreement, the Sellers had both a site plan and a geological report prepared, which both identified a fault or fault trace on the land, and which required the Sellers to relocate their winery’s building pad from its original planned location in order to provide a 50-foot setback. These were not disclosed to the Buyer.

The Buyer sued, and the trial court ruled for the Seller, finding that the disclosure requirement was “merged in the deed” when the parties closed escrow. Buyer appealed. The trial court ruling was on summary judgment, meaning the court said that there was no issue of fact which a judge or jury could go either way.

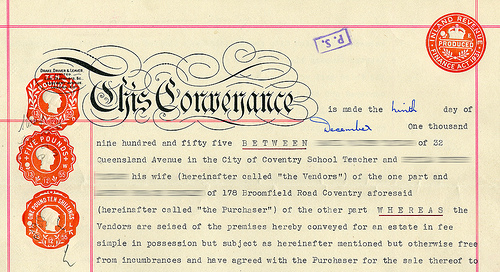

In this case the deed apparently had the typical language like “For a valuable consideration, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, Seller Grants to Buyer the following described real property in the County…” The court found it a “rather pedestrian instrument addressing only “the mechanics of transferring title” and containing a legal description of the property conveyed.” It concluded that, from the face of the deed itself, it appears that not all of the terms of the contract were “merged” into the deed.

The Sellers argued that the sole purpose for the disclosure covenant was to aid the buyer in doing its due diligence investigation to determine whether or not to go through with the deal. Once the buyer decided to close the transaction, it gave up any claim for breach of the disclosure obligation.

The Sellers argued that the sole purpose for the disclosure covenant was to aid the buyer in doing its due diligence investigation to determine whether or not to go through with the deal. Once the buyer decided to close the transaction, it gave up any claim for breach of the disclosure obligation.

But the Buyers countered with a declaration stating that their understanding was that the covenants would survive closing. There was no agreement that the covenants and warranties would merge in the deed and be extinguished at the close of escrow. Rather, it was the buyers’ intention that these provisions in the purchase and sale agreement would continue to be enforceable after close of escrow.

The court of appeal agreed with the Buyers. The declaration provided by the Buyers should be considered in figuring out the parties’ mutual intent on the survival issues. Thought the purchase and sale agreement had several paragraphs that specifically provided for their own survival after close of escrow that alone does not compel the conclusion that no other provisions could survive without similar language.

I agree that there may be triable issues of fact. The fact that some of the covenants had language stating that they survive closing is a strong argument for the Sellers. But, stepping back and viewing from the distance, it appears that the Seller deliberately withheld these reports from the Buyer. The Seller had to relocate the site it planned to build on. This bad conduct may influence the factfinder enough to overcome the Sellers arguments at trial.

Photos:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/sharonhahndarlin/12604189833/sizes/m/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/joybot/6310306480/sizes/m/

California Real Estate Lawyers Blog

California Real Estate Lawyers Blog